The stories of refugees and internally displaced persons are always filled with pain, trials, and hope. These are narratives that awaken empathy and touch the hearts not only of compatriots but also of people of various nationalities and faiths.

Norwegian Terje Holmedal spent three years in Azerbaijan, working and learning about the country from the inside. During his time there, he met a displaced girl from territories occupied by Armenians. The fate of this girl from Jabrayil, forced to leave her home during the First Karabakh War and deprived of the opportunity to study, left a deep impression on him.

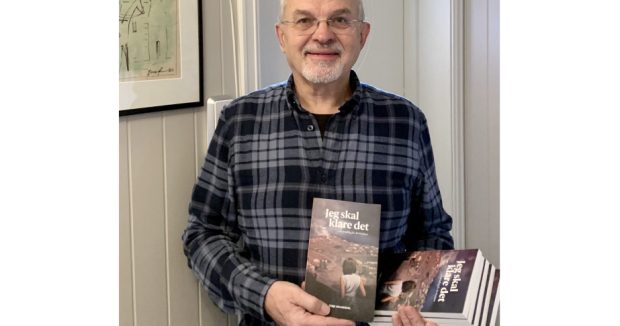

Her experiences and strength of will became the foundation for Holmedal’s debut book Jeg skall klare det (“I Will Manage”), published in 2021. The heroine of the book was named Lala and became a composite image of all those who endured the trials of war and exile.

In an interview with AZERTAC, the writer shared what motivated him to address the topic of forced displacement and how Lala’s story turned into a literary project.

— Terje, how did your life become connected with Azerbaijan?

— My first acquaintance with Azerbaijan was in 1995. At that time, I worked at the headquarters of the Norwegian Santal Mission, which cooperated with the British organization Global Care and was later registered in Azerbaijan as an independent NGO called Norwegian Humanitarian Enterprise (NHE). The organization provided support to orphanages, schools, agriculture, fish farming, and cultural projects, and from the very beginning worked with internally displaced persons in Ganja and Sheki.

I was responsible for selecting and accompanying staff sent abroad and had to become familiar with the conditions in which our representatives worked. I discovered a country severely affected by the collapse of the Soviet Union and going through very difficult times. A particular challenge was the large number of internally displaced persons concentrated in cities. The authorities appreciated our team’s efforts — distributing food and clothing and, no less importantly, providing moral support to people who had lost their homes.

In 2006, I was appointed head of NHE’s office in Azerbaijan and remained in that position until 2009. When my wife Annelise and I arrived in the country, NHE already had numerous ongoing humanitarian and development projects.

Among these projects was an agricultural program that included training farmers and introducing livestock artificial insemination techniques. Soon, we launched a major microcredit program, which was warmly welcomed by both the population and the authorities. Most of its clients were internally displaced persons who used the opportunity to start their own businesses and secure a stable income.

It was truly exciting to witness how Azerbaijani society gradually regained its identity and built modern infrastructure.

— How did you meet Lala — or, as her real name goes, Shafag?

— In addition to the projects mentioned above, we also cooperated with several orphanages. It was difficult to meet children from disadvantaged families: some were orphans, others had disabilities.

Our team visited the orphanage in Mardakan three times a week. Many of the children were in severe conditions, and the assistance they received at the time was extremely limited. Today, the situation there is significantly better.

My wife led the project and managed a team of staff and volunteers who regularly visited the orphanage. At first, Annelise did not know Azerbaijani, so we decided to hire a local part-time worker.

This person turned out to be a young student, Shafag — an internally displaced person living in Baku with her mother. Meeting the children with disabilities made a strong impression on her.

— What prompted you to write a book specifically about an Azerbaijani internally displaced person?

— One day, in 2007, a Norwegian journalist visited us to prepare a story for his publication. He interviewed our translator. I listened to her story and realized that her life contained so much tragedy and strength of will that one day it definitely deserved to be turned into a book.

The idea of putting her story on paper never left me. I had always dreamed of trying my hand at literature, and after retiring in 2017, that dream began to take shape. I wrote about it on my blog, and several friends encouraged me, saying that Shafag’s story in particular deserved to be told.

In the fall of 2019, I decided to return to this idea. I already had a ticket to Azerbaijan for the summer of 2020, but the trip was canceled due to the pandemic. I then wrote a letter to Shafag, explaining my plan and asking if I could base a book on her life. By that time, she was already an adult, and I knew her husband.

Shafag was touched and grateful that someone wanted to tell the story of internally displaced persons. She gave me permission to draw upon her personal experience.

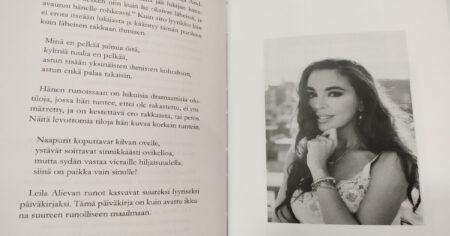

We exchanged many letters but only met again when the book was published in 2021. In the book, I named her Lala. Most of the plot is based on real events, including the episode that gave the book its title, “I Will Manage.” Lala could not attend school, but at the age of 12, she finally sat at a desk and firmly resolved to catch up with her peers.

— How difficult was it to write about a real tragedy while maintaining a literary form?

— I was very clear that I wanted to write a story that accurately reflected the reality I encountered in Azerbaijan, as well as the society I met there and for which I have great affection. I also felt a strong sense of respect for Shafag, who allowed me to tell her life story.

The tragic story of war and displacement intertwines with the story of a hospitable and warm society, where people genuinely care for one another. I derived great satisfaction from conveying this in writing.

At the same time, as I was writing and following the developments of the conflict almost in real time (in 2020), it affected me deeply. I vividly remember Shafag sharing messages from the President’s assistant reporting from Jabrayil, stating that “everything is destroyed” there. For me, this became an opportunity to share my own experiences in Azerbaijan while simultaneously drawing attention to the lives of people facing injustice.

The literary form allowed me to imagine and develop the plot. The parallel storyline about the person who later becomes the heroine’s husband is fictional. The same applies to her friends, who play an important role in her transition to adulthood.

— How was the book received in Norway? Do Norwegians understand what Azerbaijani internally displaced persons went through?

— The book was received surprisingly well in Norway. Many Norwegians say that the story feels authentic. But of course, that doesn’t mean they fully understand the situation of internally displaced persons. At the same time, more and more people here have friends among refugees from Syria and Ukraine…

In my opinion, the response I received was simply amazing.

— Did you receive feedback from Azerbaijanis after the book was published?

— Unfortunately, the book is only available in Norwegian. I made a simple translation into English and shared it with a few friends in Azerbaijan. They gave me positive feedback. Of course, I was most eager to hear the reaction of Shafag herself. She said she recognized herself in the heroine, and she even liked the parts I had invented myself.

I have been invited multiple times to events organized by the Azerbaijani diaspora in Norway, including a memorial ceremony dedicated to the 30th anniversary of the Khojaly tragedy in 1992.

On May 15, 2022, I had the honor of participating in an event dedicated to the Year of the City of Shusha, where I was invited by the head of the CAN organization, Shervin Najafpour. On that day, I read an excerpt from my book.

— How did three years of living in Azerbaijan change you, and what do you remember most about the country?

— First of all, I would say that the three years I spent in Azerbaijan were the best years of my professional life. I felt that the people in this country welcomed me and the NHE organization, highly valued our work, and appreciated what we were doing. I became a person more open to myself and my own feelings. In addition, I developed many close and warm friendships, which make me want to return to Azerbaijan again and again. I last visited in the fall of 2024.

I traveled extensively across the country, met many people, and always felt their respect and attention. Some of my most vivid memories are connected to sharing meals with people, especially in rural areas. Sitting at a table in a garden or on a veranda, enjoying amazing Azerbaijani dishes, listening to toasts, and being part of a big family at that table…

Moreover, I vividly remember that in difficult moments — whether problems arose on the road or at home, in the apartment — there was always someone who came and helped to resolve everything.

I have several favorite restaurants and places that I always return to whenever I visit the country.

— You mentioned that at the time your wife did not speak Azerbaijani. Does she speak it now? And what about you?

— Yes, my wife has learned Azerbaijani quite well. I also know Azerbaijani at a sufficient level to communicate freely. This allows us to feel a special closeness with people. Especially in rural areas, people greatly appreciate that we can speak their language. Every time we return to Azerbaijan, we worry a little: have we forgotten the language? But no, it always stays with us!

Also — I really enjoy traveling around the country using public transport: buses, trains, and the beautiful Baku Metro.